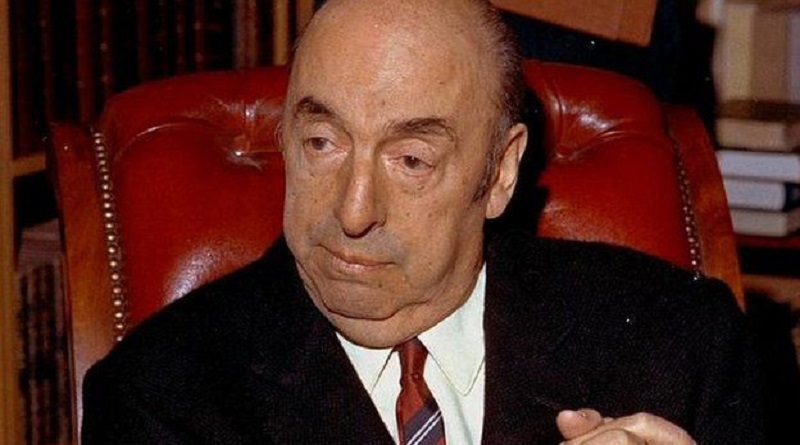

Pablo Neruda on the 50th anniversary of his death: ‘Come and see the blood on the streets’

BY Harsh Thakor

On 23rd September we commemorate the 50th death anniversary of Pablo Neruda, whose contribution to revolutionary poetry was path breaking.

The flow of Neruda’s poetry reminded one of a river, while it’s symmetry was reminiscent of path breaking monument created. His poetry was similar to carved wood, penetrating social reality at it’s deepest core. Often there were subtle changes in his style of writing; giving vibrations of an artist being re-born.

One got sensations of the earth shaking in his poetry. Noone in a more lyrical manner manifested the aspirations of the toiling workers and peasants, the ground reality of struggles, or the essence of Marxism. Neruda’s style of narrative was unique, one of it’s very own kind.

The Spanish Civil War is what lit the spark to give birth to Neruda as a revolutionary. It made him permanently shed bourgeois romanticism, or sentiment or individuality and integrate with a collective cause. Neruda’s evolution or crystallisation into a Communist is one of the most intriguing or heart touching stories.

Neruda defied fascism at it’s hardest point with his poems igniting a prairie fire in the hearts of masses world over, to give a blow to colonialism and fascism. Rarely had any poet touched the core of the soul of the people, to stand up against oppression.

Neruda wrote poems symbolising the role of Stalin in constructing a Socialist Society and playing role of the saviour of world people in World War 2 against Hitler, Mao Tse Tung creating an extraordinary transformation in China like no third world county or Fidel Castro in Cuba later and on Che Guvera’s being role model of a new Socialist man.

No overseas poet was such a mascot in projecting the egalitarian nature of Socialist Societies as Pablo Neruda., be it USSR, China or Cuba. He was like a boulder who could weather the most powerful storms.

Neruda devoted a great art of his life to travel, to his readings of his magnificent verse and to his relentless service to the cause of Communism. He worked laboriously at the World Peace Conferences, at the various writers’ conferences, for the Lenin Peace Prize, for the academies of Eastern Europe and of South America.

He condemned the dictators and tyrants, against the persecution of writers. He lived amongst reknowned stalwarts as the Turkish Communist poet Nazim Hikmet, the Colombian novelist Gabriel Garcia Marquez, the Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral, the French poet Paul Eluard, the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, the Cuban poet Nicolás Guillén and the Brazilian novelist Jorge Amada, among others.

Neruda spoke for them when he told the Continental Congress of Culture in May 1953, “We are writing for modest people who, very, very often, cannot read. And yet, on this earth, poetry existed before writing and printing. That is why we know that poetry is like bread, and must be shared by everyone, the literate and the peasants, by all our vast, incredible, extraordinary family of peoples.”

Neruda was always a man who relished company of the people more than power. As a young consular official in Rangoon (then part of British India), Neruda abhorred the colonial caste system. He loathed the British officials because “they were monotonous and even ignorant,” and kept company with native Burmese people (including a lover, Josie Bliss) for which the British expelled him from their social institutions.

“Those intolerant Europeans were not very interesting,” In his memoirs, Neruda narrated the ruthlessness of British colonialists towards native culture: “This terrible gap between the British masters and the vast world of the Asians was never closed. And it ensured an inhuman isolation, a total ignorance of the values and the life of the Asians.”

Wherever Neruda went, from Ceylon in the 1920s to Italy in the 1960s, he endeavoured to traverse worlds of the people much more than the cushions of power.

Fresque en l'honneur de Salvador #Allende et de Pablo #Neruda à Vitry-sur-Seine pic.twitter.com/v1dJeYuriT

— Le Rouge-Tricolore (@RougeTricolore) September 20, 2023

Life Story

Neruda came into this earth as Ricardo Eliecer Neftali Reyes Basoalto on July 12, 1904, in Parral, central Chile. His mother died shortly after his birth, but he established very good relationship with his stepmother. His father, a driver of a ballast train on the emerging railway, often carried him as a child on journeys through the countryside of his region, and so he observed the hard physical labour of the railwaymen, who transferred stones and sand between the sleepers so that the heavy rain would not shift the tracks. This experience sowed the seeds of Neruda’s poetry and later became the central theme of the nature poems of Canto General.

In 1921, Neruda ventured on a French course at Santiago University but soon abandoned it. Living amidst poverty, he gradually politicized.. In 1923, he published a first collection, Book of Twilights, which indicates “he will be counted among the very best, and not only of this country and of his era.” This was followed in 1924 by the poetry collection Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair, which was a landmark.

Now Neruda embarked on diplomatic missions to Singapore and Java, where in 1930 he met his first wife María Antonieta Hagenaar Vogelzang (Maruca), with whom he returned to Chile in 1932. Neruda was appointed vice-consul in Buenos Aires in 1933.

Here he met Federico García Lorca, who became his close friend. At this time Neruda wrote to a friend: “It seems that a wave of Marxism is criss-crossing the world. Letters I receive [from] Chilean friends are pushing me towards that position. In reality, politically speaking, you cannot be anything but a Communist or an anti-Communist today.” But, he continues, “What is true is that I hate proletarian, proletarianizing art.” He was soon to radically change this position.

In the early summer of 1934, Neruda went to Spain with post of consul, first to Barcelona—the consul in Madrid was Gabriela Mistral. In Madrid, Neruda renews his friendship with Lorca. In October, a seriously ill daughter was born to Neruda. He translated William Blake’s “Visions of the Daughters of Albion” and “The Mental Traveler” into Spanish. In addition to Lorca, Neruda met other leading poets of the time: the Spaniards Rafael Alberti and Miguel Hernández, as well as the Cuban Nicolás Guillén. In June 1935, with fascists firmly entrenched in Germany, Italy, and Portugal, Neruda took part in the First International Congress of Writers for the Defence of Culture in Paris.

In Madrid, Neruda met his second wife, Delia del Carril, a communist 20 years his senior. who he married in 1943. Under her influence, as well as witnessing events in Spain, Neruda was drawn toward a communist position and grasped the role of art in the political struggle:

I began to become a Communist in Spain, during the civil war.… That was where the most important period of my political life took place—as was the case for many writers throughout the world. We felt attracted by that enormous resistance to fascism which was the Spanish war. But the experience meant something else for me. Before the war in Spain, I knew writers who were all Republicans, except for one or two. And the Republic, for me, was the rebirth of culture, literature, the arts, in Spain. Federico García Lorca is the expression of this poetic generation, the most explosive in the history of Spain in many centuries. So the physical destruction of all these men was a drama for me. A whole part of my life ended in Madrid.

Neruda’s poem created an explosive reaction from the world’s concerned people about the events in Spain. He forced his government to help as he saved two hundred refugees from the battering from Franco’s rule and from concentration camps – they travelled to Chile and many later helped Neruda in his time of crisis. The poem’s service to the oppressed social classes and to the struggles of the left changed the way Neruda wrote. When he returned to Chile, he stood before the porters’ union in Santiago’s main market, and read España. The porters’ did not seem to react, then after a moment silence,

“This man, with a sack around his waist like the others, got up, leaning with his large hands on his chair, looked at me and said: ‘Comrade Pablo, we are totally forgotten people. And I can tell you that we have never been so greatly moved. We would like to say to youŠ’ And he broke down in tears, his body trembling with the sobs. Many of those around him were also crying. I felt a knot form in my throat.”

Neruda made a drastic transformation from the abstraction of his poetry, and converted his passions and his visions into verses readable to those who had not the luxury of an advanced education. The workers, after this Santiago experience, became his readers and listeners. Neruda wrote for them. In his great poem, Explico algunas cosas, “Let Me Explain a Few Things,” Neruda described his stylistic shift,

“You will ask: And where are the lilacs and the metaphysics petalled with poppies and the rain repeatedly spattering its words, filling them with holes and birds? You will ask why his poetry Does not speak of dreams and leaves, And of the great volcanoes of his birthplace? Come and see the blood in the street.

Come and seeThe blood in the streets. Come and see the blood In the streets!”

In Chile, Neruda delivered readings to ordinary workers. One such reading from his volume Spain in Our Hearts for the Porters’ Union was a revelation in 1937:

Spain’s bloodshed , the terrible suffering of its people penetrated the memory of the victimised people in the history of South America: Memory flashed as a central theme of his poetry with the poet remaining a a witness. Memory was the essence of the Canto General, completed underground ten years later.

The soul searching theme of Canto General was unravelling the history of South America to the present, the liberation movements, and the anti-imperialist struggle. It traced the protagonists of the historical process, from the working people of Machu Picchu, descendants of the Incas.

Commenting on Canto general in Books Abroad, Jaime Alazraki remarked, “Neruda is not merely chronicling historical events. The poet is always present throughout the book not only because he describes those events, interpreting them according to a definite outlook on history, but also because the epic of the continent intertwines with his own epic.”

Critique Bizzarro noted, “In [the Canto general], Neruda was to reflect some of the [Communist] party’s basic ideological tenets,” the work itself is far more than propaganda. Looking back into American prehistory, the poet examined the land’s rich natural heritage and described the long defeat of the native Americans by the Europeans. He concentrated on elements of people’s lives common to all people at all times.

In early 1939, the democratic President Pedro Aguirre Cerda, elected in December 1938, appointed Neruda special consul in Spain and designated him with the role of undertaking the immigration of Spanish refugees. Neruda ensured the flight of about 2,000 Spaniards to Chile. At the end of the year, Neruda and Delia returned to Chile. The next consular post was in Mexico.. After the 1941 German invasion of the USSR, Neruda actively supported the Soviet Union and wrote the heart touching “Song for Stalingrad,” which illustrated most lucidly the collective experience of the USSR people confronting the Nazi armies from the depths of despair. It sang a song in the very core of oppressed people’s hearts all over, reverberating why Stalingard was the turning point in history of mankind.

In 1944, a year before he formally joined the Communist Party, Neruda successfully carried the Communist ticket for the Chilean Senate. As a delegate of the people, Neruda condemned the subjugation of of the Chilean economy by the US transnational corporations, of the

Violation of freedoms for the working-class by the government, and of the autocratic steps made by the President in light of the Communist-led strikes among the mine-workers (copper being Chile’s main export). Angered by Neruda’s turbulence in parliament, the President named him persona non grata and called for his arrest. Neruda jumped underground, where he took shelter with his friends, of those whom he had rescued from Spain and of the Communist Party.

50 years on, The Death of Neruda 4.30pm Sunday @BBCRadio4 contemplates the troubled legacy of Chile's most celebrated poet. With Isabel Allende, Ariel Dorfman, @Guille_x77 @SantiagoC @AdamFeinst presented by @mmdelgado1 & produced by @joglanville1 #Neruda https://t.co/NVCtHRVYK2

— Emma Harding (@EmmaHarding01) September 14, 2023

Neruda Poetry

During his years in the parameter of the underground, Neruda composed the major part of his greatest work, his Canto General. This work literally transcended region unexplored in revolutionary poetry ,like a pth breaking experiment.

In one section of this epic poem that encompasses the length of the continent of the Americas and the history from pre- Columbian times to his present, Neruda related the immediate Theme for his flight,

“And atop these calamities a smiling tyrant spits on the betrayed miners’ hopes. Every nation has its sorrows, Every struggle its torments, But come here and tell me If among the bloodthirsty, Among all the unbridled Despots, crowned with hatred, With sceptres of green whips, There was ever another like Chile’s?”

In Canto General, Neruda included a section that was also published independently, in “The Heights of Macchu Picchu” (1948). Neruda had visited the ancient Inca ruins of Peru in 1943, and he had been amazed not only by the greatness the ancient history of the Americas, but also of the vista this gave him. At 8,000 feet, the city which had been built in the middle of the 15th Century, paved way for Neruda to explore history of the continent from its ancient past to the present, and from North to South.

From the Heights, Neruda summons this great American voice, as he begins to narrate the story of Columbus, the conquistadors, the resistance of Tupac Amaru, the Bolivarian revolution, the betrayal of its hopes to his present. The Canto was Neruda’s greatest poem.

Political targeting forced him to go underground for about a year in 1948, where he finished Canto General. In late February 1949, he fled across the Andes to Argentina. From there; he made his way to Europe. During this period underground, Picasso championed him at the first World Congress of Intellectuals for Peace in Wroclaw, Poland, in July 1948, as “one of the greatest poets in the world.”

Neruda, newly arrived in Europe, participated in the First World Congress of Partisans for Peace on April 20, 1949, alongside Picasso, Paul Robeson, and many others. Neruda remained in Europe until 1952 and travelled to many socialist countries. He started a relationship with Matilde Urrutia, who becomes his third wife in 1966.

The year 1959 also witnessed the Cuban Revolution, and Neruda hailed it with his book of verse Song of Protest.

From “To Fidel Castro”:

And Cuba is seen by the southern miners,

the lonely sons of la pampa,

the shepherds of cold in Patagonia,

the fathers of tin and silver,

the ones who marry cordilleras

extract the copper from Chuquicamata,

men hidden in buses

in populations of pure nostalgia,

women of the fields and workshops,

children who cried away their childhoods:

this is the cup, take it, Fidel.

It is full of so much hope

that upon drinking you will know your victory

is like the aged wine of my country

made not by one man but by many men

and not by one grape but many plants:

it is not one drop but many rivers:

not one captain but many battles.

He visited China three times and left behind innumerable poems expressing his admiration for the country. Neruda’s poems portrayed most lucidly how anew Socialist man was given birth in China writing anew epoch in history.

In 1949, he praised Chairman Mao Zedong for transforming the future of tens of millions of people. In 1950, Neruda inscribed “Long Live Mao!Long Live the Chinese People!” on a Chinese edition of the collection of his poems. Premier Zhou Enlai lauded Neruda as the first swift heralding the spring of China-Latin America friendship.

In 1951, Neruda made his second visit to China. He contrasted the conditions to his first trip some 20 years ago when he saw a place ruined by war, deprivation and degradation Now the country had changed 360 degrees, in Neruda’s eyes.. He held the Chinese people in great esteem for having the best smiles in the world. , wearing a smile in the face of ruthless colonialism, revolutions, famines and slaughters..

Passionate about China, Neruda jotted down what he saw and learned during the short journey into a long poem called Ode to New China to celebrate the birth of the new country. In the poem’s last section, Salute China, he wrote:

Now, people all over the world have seen that

your vast land has been unified and

you are as swift and strong as tornado.

Your sharp ax swings towards the villains and

your light of victory strikes at the enemy.

Oh, the triumphant republic

embraces the territory with your arms and

lays the foundation for your eternal peace!

In his third visit to China in 1957, Neruda witnessed even more remarkable changes. When he last visited the country, the men or women on the streets wore tattered uniforms. Five years on, the Chinese people were clad in clothes with better quality.. He asserted that “this nation was not capable of making anything ugly and even the most primitive straw sandals were like flowers made of hay. “

When Neruda went to New York in 1966 to attend a meeting of the PEN Club as a guest of honor, Cuban writers labelled as a traitor in an open letter. However, this never affected Neruda’s overwhelming support to Cuba.

Salvador Allende stepped into Chile’s political stage as a socialist presidential candidate in 1952. Opposed to the reactionary Videla regime, his program propagated the nationalization of Chile’s mineral resources. Neruda again supported Allende in the 1958 election campaign.

In early 1969, the poet again supported the election campaign of the Chilean Communist Party and became its presidential candidate in September—a candidacy he forfeited January 1970 in favour of Salvador Allende, who would then be the sole left-wing candidate. From mid-July he was actively involved in the election campaign for Allende, who won the election on September 4, 1970.

In November 1972, Neruda returned to Chile, with his health in a precarious state. Nevertheless, he toiled on his poetry and completed his memoirs. On September 11, 1973, he heard news of the putsch, the bombing of La Moneda Palace, and the death of President Allende.

Pablo Neruda died on September 23. Neruda’s funeral on September 25 at the Cementerio General in Santiago was he first spark of a popular revolt, despite an overwhelming military presence.

His another famous poem reflect harsh reality of even today’s world. it is about Spanish war. Last few lines of long poem ‘I\’m Explaining a Few Things’-

Treacherous

generals:

see my dead house,

look at broken Spain:

from every house burning metal flows

instead of flowers,

from every socket of Spain

Spain emerges

and from every dead child a rifle with eyes,

and from every crime bullets are bom

which will one day find

the bull’s eye of your hearts.

And you will ask: why doesn’t his poetry

speak of dreams and leaves

and the great volcanoes of his native land?

Come and see the blood in the streets.

Come and see

the blood in the streets.

Come and see the blood

in the streets!

(Harsh Thakor is a freelance journalist. Thanks information from ‘The Paris Review ‘b Mark Eisner, The Marxist of April-June 2004 by Vijay Prashad, ‘Poet of the People’ in New Republic by Benjamin Kunkel.)

Do read also:-

- Labour in ‘Amrit Kaal’ : A reality check

- Discovering the truth about Demonetisation, edited and censored, or buried deep?

- Class Character of a Hindu Rashtra- An analysis

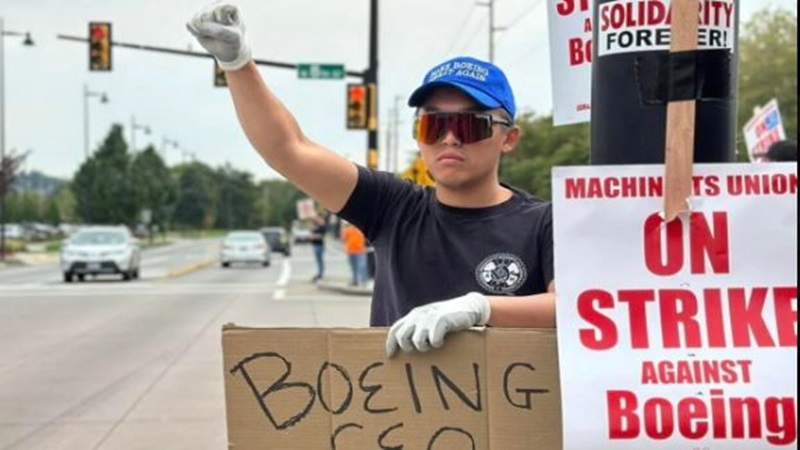

- Gig Workers – Everywhere, from India to America, from delivery boys to University teachers

- May Day Special: Working masses of England continue to carry the spirit of May Day through the Year

- New India as ‘Employer Dreamland’

- Urgent need for reinventing Public Sector Undertakings

Subscribe to support Workers Unity – Click Here

(Workers can follow Unity’s Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. Click here to subscribe to the Telegram channel. Download the app for easy and direct reading on mobile.)