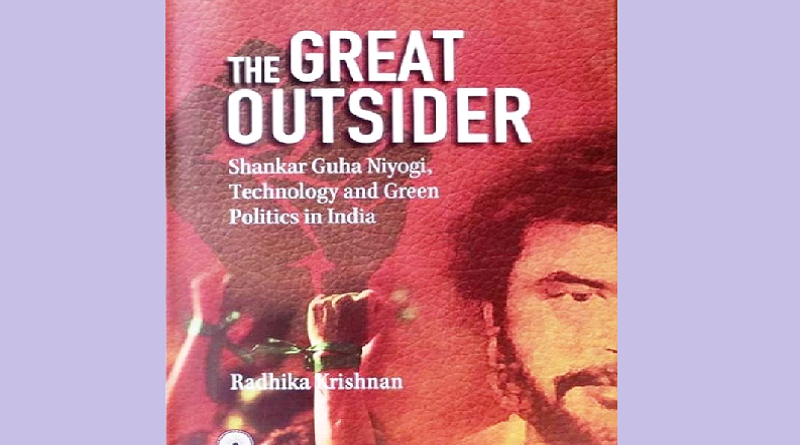

The great Outsider Shankar Guha Niyogi: Technology and Green Politics in India- Book Review

By Annavajhula J C Bose, PhD

Published in early 2023 by the Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla, this book is a heartfelt as also intellectually strong homage to the all-in-one alternative trade unionism pioneered by the late Shankar Guha Niyogi.

The author (pictured below) is an electrical engineer turned into a leading and intrepid “eco-technological-labour” investigator in India. Her work in India is a definitive and pathbreaking add-on to the knowledge assembled in The Palgrave Handbook of Environmental Labour Studies.

This book is based on Radhika’s doctoral research which I value most. It passionately takes us back to the tumultuous period of the 1970s and 1980s in post-independent India—“a period marked by the emergence of new social forces, new ideas and ideologies, fresh challenges to narrative of ‘development’ that were considered hegemonic in the preceding decades”.

And it “touches briefly upon the myriad experiments and experiences of the Chhattisgarh Mukti Morcha from the time of its formation in 1977 to 1991 when its founder secretary and leader”, Shankar Guha Niyogi, “was murdered.”

The book is divided into four chapters, supplemented by very interesting footnotes and bibliography.

In the introductory first chapter, we come to know the voices of protest in peasants/farmers, workers, Adivasis and environmentalists against the state-sponsored, capital-intensive, high-technology driven model of modernization initiated in India. “The peasant movement articulated the demand for establishment of agro-based small and medium-sized industries and for bringing industrial development in harmony with the development of agriculture.

The growth of kulak movements and a powerful middle peasantry demanding lower input and higher output prices in the agricultural sector has been traced to the Green Revolution and its contradictions.

The workers’ movement too occasionally acknowledged the impact of technology, as is evident from the textile workers’ strike in Bombay and the fisherpeople’s movements in Goa and Kerala. This was also a period when environmentalists, in the backdrop of the Bhopal gas tragedy, were bringing labour to the debate—arguing for stronger workplace legislations related to occupational health and safety along with pollution.”

The Chhattisgarh Mukti Morcha (CMM) emerged in this milieu in relation to the Bhilai Steel Plant (BSP) set up in 1959 as an epitome of the Nehruvian industrial project of transforming the Indian economy and rural landscape. It emerged as “the voice of the worker, peasant and the Adivasi struggling to cope with new challenges”.

Its various campaigns captured the moods of anti-dam sentiment, the passionate struggle to defend forests against monocultures, the anger against retrenchment caused by mechanisation, the alienation from land and rivers along with a solid plan for semi-mechanisation of iron ore mining to defend human labour in order to reconcile industry with employment and livelihoods with ecology.

The second chapter is an elaboration of how the CMM represented the concerns and interests of the working class, especially the contract workers, by shaping the industrial wage labourer and the farmer as a defender of the environment; and by factoring in how this clashed with overwhelming cultural notions around the Adivasi feted as a green warrior and a bulwark against modernity. The CMM addressed the inter-connected discontents of peasants, workers, farmers and Adivasis.

Its critique of India’s forest policy and Green Revolution; its choice to echo the voice of those affected by water pollution as well as over-extraction by large-scale industries; its respect for tribal cultural spaces and histories; its opposition to large dams and canals and support for small-scale stop dams and lift irrigation systems; its attempts to reclaim lost knowledge about local eco-systems, and to restate enduring connections between communities and the forest eco-systems; its defence of biodiversity; its opposition to the ruination of local economies; its commitment to alternative technological/developmental regimes, and its struggles for fair wages, enhanced bonuses, provision of provident funds, gratuities, leave, better working conditions, and more facilities for the workers and their families like housing benefits, and so on are all perfectly exemplary.

The CMM with its “red and green” flag was indeed an eminent case study of “green political and electoral articulations in India” although it failed to emerge as a “Green Party” like in Europe.

The third chapter is about how the CMM clearly gave itself the mandate of critiquing and engaging with technological designs, and in the process how it inserted itself, in vain though, into the ‘developer’ environment of technology. We also come to know how the workers were denied by the management the desire to democratically control the workspace and avail themselves of higher wages on achieving the capability to enhance production and efficiency! “The CMM fought spirited battles before the management of the Bhilai Steel Plant agreed to implement its plans for semi-mechanisation in the Dalli Rajhara iron ore mines. The successful implementation of these proposals nevertheless proved to be inadequate. By the mid-1990s, BSP had reverted to its original plans for complete mechanisation of the mines despite the CMM’s resistance and the proven track record of semi-mechanisation.”

Finally, we come to the conclusion that “Niyogi’s legacy—of organizing workers; forcing the world to see and hear Chhattisgarh’s Adivasis; building a hospital for workers; speaking up about environmental concerns that are inconvenient to industrialists and ruling politicians alike—was and continues to be a threat to corporate interests and majoritarian politics, not just to local industrialists. Just as Niyogi was seen as a Naxalite and thus too seditious to be a BSP employee in the late 1960s, those who walk in his path too have been persecuted and framed under draconian laws.”

All the same, we must reckon with the fact that “There are countless instances of trade union and peasant organizing on the Left, which emphasize struggles not only for wages at the workplace, but for social dignity, freedom from caste and gender-based violence, for clean drainage, unpolluted water, homestead land, housing, education and healthcare. Niyogi would certainly recognise such organisers as his comrades.”

To conclude, this book emphasises the importance and relevance of the alternative trade union models and practices that the CMM and the like symbolised. Also, Shankar Guha Niyogi remains an unforgettable inspiration for the underdogs and their representatives to face the dark times.

Let hundreds of Shankar Guha Niyogis blossom in India. For, “Niyogi was attempting to bring to the fore the voice of the Adivasi and that of the subsistence peasant and agricultural labourer; the resistance he was framing as a trade unionist organising mineworkers and factory labourers was thus essentially a resistance that refused to overlook the imaginations of the Adivasi and the peasant.

It was the framework of a peasant who was yet to fall under the hegemony of the idea of heavily-mechanised farming; that of the Adivasi who was concerned about dwindling livelihood options in the village; and that of the worker who retained tenuous and even mixed memories of different forest-based livelihood patterns. It was, moreover, an imagination that appreciated close connections to land, forests, rivers and human interventions in order to forge organic and sustainable links with them.”

This short book of 113 pages based on Radhika Krishnan’s doctoral research on Niyogi and his campaigns is densely packed with all the issues concerning the future of the Indian weak and vulnerable people at large, and so must be read and discussed.

References:

Radhika Krishnan. 2016. Red in the Green: Forests, Farms, Factories and the Many Legacies of Shankar Guha Niyogi (1943-91). South Asia Journal of South Asian Studies. September.

(Writer teaches in Department of Economics, SRCC, Delhi University.)

- Labour in ‘Amrit Kaal’ : A reality check

- Discovering the truth about Demonetisation, edited and censored, or buried deep?

- Class Character of a Hindu Rashtra- An analysis

- Gig Workers – Everywhere, from India to America, from delivery boys to University teachers

- May Day Special: Working masses of England continue to carry the spirit of May Day through the Year

- New India as ‘Employer Dreamland’

- Urgent need for reinventing Public Sector Undertakings

Subscribe to support Workers Unity – Click Here

(Workers can follow Unity’s Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. Click here to subscribe to the Telegram channel. Download the app for easy and direct reading on mobile.)