The Precarious Migrant Worker, The Socialization of Precarity- Book Review

By Annavajhula J C Bose

The two books on migrant work in the West, taken up for review here, are written by down-to-earth organic intellectuals.

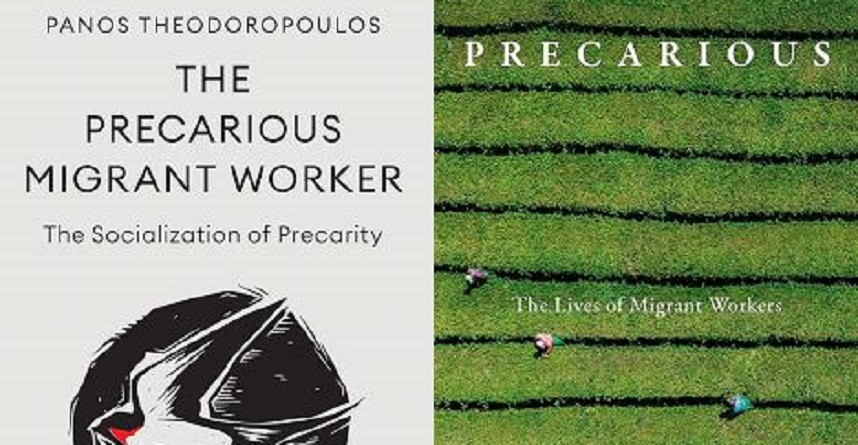

Panos Theodoropoulos. 2025. The Precarious Migrant Worker: The Socialization of Precarity. Polity Press. E-Book ISBN: 978-1-509-56500-9. Pages 224. Price $20. June.

&

Marcello Di Cintio. 2025. Precarious: The Lives of Migrant Workers. Biblioasis. E-Book ISBN: 9781771966603. Pages 342. Price $24.95 CAD. September.

That means, the authors have played, by Gramsci’s Marxism, the role of articulating the experiences of the migrant working people in relation to the challenge of changing the existing power structures of capitalism militating against their welfare at least in the sense of ILO’s decent work agenda.

Panos Theodoropoulos (PT, hereafter) had, in fact, worked as a Greek migrant worker in Bradford and Glasgow before completing his sociological PhD and becoming an academic at King’s College, London.

And Marcello Di Cintio (MC, hereafter) has excelled in writing via ethnographic research about a variety of real-world people—Palestinians, taxi drivers, sex workers—including, lately, migrant workers in Canada.

Their experiential and empathetic communication of the human condition of the migrant workers is corroborated by some other research as well in Europe and North America.

These two books must now be read on two counts. First and foremost, they help us overcome the drawback of Marxists in understanding why there has been the failure of class consciousness and popular rebellion to take hold in western industrialized countries.

In the process, they also make us understand why there has been ineffective labour governance since long. Secondly, they serve the purpose of educating the public to transcend the malicious right-wing populist demagoguery and misgivings against the immigrants that is now rampant everywhere in the world.

And related to this, it is high time the so-called non-migrants (citizens) of the host country or state within a country saw the immigrants and related to them as not “subhuman, nonhuman, non-anything” value-producers. They need to understand the push factors spurring migration such as debt crises, austerity and lack of opportunity in the countries of migrant-origin (Eastern and Southern Europe, for example, in Europe).

Conflicts, disasters, mindless urbanization alongside destruction of rural livelihoods, generalized violence and human rights violations also lead to forced displacement and migration in terms of refugees and asylum seekers.

Nearly every migrant worker that MC spoke to had been done wrong. “Cheated. Threatened. Beaten.”

Canada’s temporary foreign worker structure is indeed “a breeding ground for contemporary forms of slavery” with excessive working hours and unpaid overtime; employers forcing workers to perform dangerous jobs or tasks outside their contracts; workers being denied access to health care, language courses, and other social services; workers being physically abused, intimidated, and sexually harassed by employers; and workers in overcrowded and unsanitary living conditions that deprived them of privacy and dignity.

MC as a grandchild of an Italian immigrant worker in Canada and evolved over time to be a patriotic Canadian bemoans thus:-

“Our migrant labour system doesn’t just provide Canadians with a supply of invisible workers to pick our strawberries, glaze our doughnuts, and bathe our elderly. The system also lowers the bar for our perceived come-from-away virtue. All an employer needs to do to be deemed a good boss—and, by extension, a good Canadian—is to treat migrant workers with the most basic humanity.”

“The system expects so little from us and tolerates so much. We don’t have to be good as long as we’re good enough. And yet still so many of us fail to meet even these low expectations. During my time with the workers, I’d seen them denied safety, wages, privacy, medical care, and justice.”

“I heard stories of fraud and violence and rape that I couldn’t adequately verify but wholeheartedly believe. I lost track of the number of workers who wept as they recounted all they’d been through for meagre promises of minimum wages. I’d heard so many accounts of workers whose lives we left in shambles they started to feel banal. Unremarkable, even. But each untold story contributes to workers’ invisibility.”

“I felt in awe of those who refused to be invisible. We should feel empathy, and responsibility, for what these workers experienced. We should also admire their agency. Their bravery. Their ferocity. We should admire too, those workers who lower their heads and silently endure. To persevere in the service of their loved ones is itself a form of resilience.”

“These workers don’t complain. Not to their employers. Not to the authorities they don’t trust. Not to the media. Sometimes not even to their own families for fear of appearing ungrateful or unmotivated or causing them unnecessary worry. But secrecy—theirs, ours—not only fortifies the delusion of our own goodness. It abets the abusers. The program’s defenders are quick to point out that the money workers send home, the PR cards they eventually earn, or the family reunions they’re finally granted, balances out whatever hardships they face.”

“Nearly all the workers I spoke to, felt their trials were worth it. But this doesn’t absolve migrant labour structures of their crimes. Just because workers might emerge grateful from the gauntlet we’ve constructed, doesn’t mean the gauntlet should persist.”

“Canada renders today’s migrants as permanent outsiders. We don’t invest in their lives beyond the cheap labour they provide because they are not one of us. We define them solely by their functionality, by the singular task we’ve hired them to do.”

“We assume they define Canada in similarly shallow terms: not a place to live but a place to work. And yet the migrants I met all transcended their low-paying jobs. They had a larger purpose than grinding out a biweekly paycheque. They worked for their futures and for the reunification of their families. They formed communities. They stood up against injustices perpetrated against themselves and others. These are the values we consider to be Canadian.”

“These are the same values my grandfather held. He brought more than just his labour to Canada. Migrant workers don’t want much from Canada. I met no worker with unreasonable expectations. They want fair wages and fair treatment. Like all of us, they want a better life. By diminishing the dignity of our most precarious workers, we diminish our own.”

PT arrived at two conclusions after a protracted period of “finding work, covertly, in Glasgow’s warehouses, factories, and kitchens, and deeply observing how the drudgery of precarity sculpts workers’ subjectivities, and also speaking with hundreds of migrant workers through formal and informal methods.”

First, “precarity is naturalised and comes to be perceived as a component of migrant worker identities. In the course of daily labour, as your body sweats and fatigues fighting for a job that is by no means guaranteed, with your ability to work being your sole vehicle for achieving some semblance of security, I saw that people converted their exploitation into a badge of self-worth”:-

“They came to identify the difficult conditions they faced not as something to be changed, but as something one must survive through, alone. Their self-worth, their identity as powerful, autonomous humans, became fused with their daily, solitary toil. This is the insidiousness of capitalism: it imprisons us precisely by relying on our desires to feel free.”

“To put it succinctly and rather crudely, in the same way that men become socialised to oppress women – and each other, and their own selves – while feeling that we are somehow doing things ‘the correct way’, workers can become socialised to oppress and exploit themselves, while being proud of it.” This is what is meant by socialization of precarity.”

“Second, there is the absence of “social movements and unions from the environments in which most working class people live and work. It is precisely due to this absence that the socialisation of precarity can take root. This reality is ignored by most texts that are written by social movements and progressive academics.”

They only write “eloquently about two million different theoretical topics and approaches, about so many things that we should do, think, or address, but they ignore the fact that social movements are entirely absent from most people’s lives.”

PT endeavours to convince people of five main things out of his book: first, immigrant labour is essential to the British economy, by design. Migrants, on zero-hours contracts, are not taking your job. Rather, the economy is structured in a way that inherently relies on migrants for specific jobs in specific sectors. Western economies are organized in a way that umbilically depends on the labour of precarious migrant workers.

“It is not migrant workers who fill vacancies undesired by the locals; rather, the real reason typically underlying employers’ calls for migrants to help fill vacancies is that the demand for labour exceeds supply at the prevailing wages and employment conditions; second, poverty is not an aberration; it is a systemic component of capitalism.”

“Our bosses understand, and value, the fact that our insecurity forces us to overexert ourselves – this anxiety directly supports their profits. Furthermore, our desires to feel free and empowered within the confines of the existing socioeconomic system may, paradoxically, fortify its foundations; thirdly, therefore, we need to seriously reconsider how we value certain behaviours, and why.”

“How do we identify with our oppression, and how are we complicit in reproducing it? Non-status-secure migrant workers are directly dependent on their employer’s goodwill and might be reluctant to unionize or otherwise claim better conditions.”

“Citizenship and migration restrictions could therefore be seen as a clear way of establishing a primary differentiation between ‘included’ and ’excluded’, but they afford the possibility of further qualifying this initial division and thereby distributing different ethnicities according to the requirements of labour markets and popular stereotypes.”

“Simultaneously, the spectacle of detention and deportation, the ultimate expression of the State’s power over migrants, is constantly operative in the background and imbues every moment with fear of expulsion. This experience is increasingly beginning to apply to previously status-secure EU migrants”;

“fourth, despite all the above, and despite the tendency to identify with components of precarity, workers nevertheless remain acutely critical of the existing social system. This awareness emerges through their experiential, material understanding of their lives as workers – in short, migrant workers understand that their exploitation is tied to their wider socioeconomic position.”

“It is only in the absence of an empowering alternative narrative that they then may re-internalise this exploitation and convert it into a badge of self-worth; and fifthly, it is high time social movements became firmly embedded in the social body; only then can the socialisation of precarity begin to be dismantled, through the development of new cultures and narratives of collective value, care, solidarity, and resistance… these narratives must emanate from accessible, physical institutions in workers’ communities, such as workers’ centres.”

The heart and soul of PT’s book is “the socialization of precarity”.

The explanation of this encapsulates the multiple complex mentalities, tendencies and behaviours that may emerge from migrant workers’ prolonged interactions with the “daily realities of precarious occupations”:-

“As their lives are constantly mediated by stress and insecurity, workers may become socialized in and through them. This socialization stems from multiple aspects that are inseparable features of precarious occupations, such as the lack of social bonds between workers, the agency arena (the constant, underlying competition with other precarious workers in the same workplace and across society), the ‘good worker paradox’ (the knowledge that, as one is attempting to as productive as possible in order to secure a job, one is also simultaneously at risk of reducing one’s necessity to the employer), and the constant pressures to perform while knowing that labour security is far from guaranteed.”

“In such precarious workplaces, precarity permeates almost all interactions, significantly disrupting the potential for the formation of substantial bonds of affinity, mutuality and trust. The stress associated with precarious occupations, where one can be fired without any protection, induces an ever-present sense of anxiety and competition amongst workers; their interdependence and coexistence, instead of being tools of solidarity, can instead be a source of added pressure which distances workers from each other. Cumulatively, these experiences can lead to a wider fortification of the conditions that breed precarity.”

“More precisely, workers are liable to internalize the conditions they face and reconstitute them into proud aspects of their identity. This individual survivalism extends to further isolate workers. This entails important complications in relation to the issue of collective action and organization, since the shared experiences of exploitation that, under different conditions, would lead to workers identifying with one another, are now interpreted as individual difficulties.”

“Even more problematically, they are difficulties which may become intimately connected to workers’ ideas of themselves, as one’s ability to overcome them by surviving through them is the measure of one’s self-worth and dignity. One’s identity as a worker is therefore attached to surviving conditions rather than changing them.”

“In this context, while instances of resistance do occur with various degrees of tenacity and success, they mostly assume the form of individualized expressions of dissent rather than collective struggle. Occupational mobility emerges as the main technique that migrant workers, especially those from the EU with some relative security in their right to remain in the UK, prefer to search for a better job. However, escaping precarity, for most, remains an unfulfilled dream.”

“Moreover, in their attempts to improve their working conditions through relying predominantly on their individual capacity to switch jobs, workers reinforce the underlying foundations of both the precarious structure and the socialization of precarity.”

The organised Left cut off from the working people’s daily lives, badly need this understanding. So also impotent global organisations such as the ILO which can never see or bring about ubiquitous decent work.

Work has become more precarious, insecure, dangerous and taxing across the Western world (Global North).

Workers seek to survive through it alone. One can imagine work’s rock bottom Darwinian race in Global South. Mistreatment at work, the withholding of wages and holiday pay, and punitive dismissals remain the daily occurrences of the migrant labour’s precarious lives.

In the absence of trade unions and other class and community-based institutions, there are charities, NGOs and state-associated employment tribunals to offer unreliable palliative help to the workers.

But their “aims and methods largely complement the modern capitalist structure”:-

“Their existence and operation mirror the wider proliferation of control throughout society, since they rely on the disempowerment of the groups they profess to help: at the same time that the welfare and penal systems place the individual in a series of conditional relationships relative to the State and fail to address the social, rather than individual, origins of poverty, these organisations come in to provide a form of relief that (1) does not challenge the foundations of the economic or social system, and (2) hinders the possibilities of autonomous community empowerment.”

In light of all this, subjecting the migrant workers to fascistic hostility and violence is unwarranted and outright inhumane.

The world has grown numb to the predicaments and trauma of the international as also national migrant workforce like it has to the harrowing stories of human suffering unfolding everyday in Gaza and Ukraine.

By Annavajhula J C Bose is Former (Economics) Professor, Shri Ram College of Commerce

University of Delhi, Delhi ([email protected])

- Labour in ‘Amrit Kaal’ : A reality check

- Discovering the truth about Demonetisation, edited and censored, or buried deep?

- Class Character of a Hindu Rashtra- An analysis

- Gig Workers – Everywhere, from India to America, from delivery boys to University teachers

- May Day Special: Working masses of England continue to carry the spirit of May Day through the Year

- New India as ‘Employer Dreamland’

- Urgent need for reinventing Public Sector Undertakings

Subscribe to support Workers Unity – Click Here

(Workers can follow Unity’s Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. Click here to subscribe to the Telegram channel. Download the app for easy and direct reading on mobile.)